History of the

Royal Guild of

Saint-Sebastian in Bruges.

Cloudy times and an unexpected lucky event (1573-1798)

Nearly the end… and yet resurrected, but with less religion (1798-1944)

Growth and prosperity in recent decades with a hopefully long and grand future (1944-present)

Some...

...introductory data

The exact founding date of the Saint Sebastian Guild in Bruges is unknown.

The oldest record of the Guild’s existence in archival documents refers to an agreement between the Guild and the Friars Minor in 1396. The Guild was probably founded a few decades earlier, around 1375.

Since it was founded, the Guild has remained continuously active until the present day, despite difficult periods, including during the Calvinist regime in Bruges and after the French Revolution. This makes it one of the oldest sports associations in the world.

Since 1573, Guild activities have taken place in the current building in the Carmersstraat. A rich heritage is preserved and the old traditions are maintained.

The Guild enjoys excellent relations with the Belgian and British Royal Families, the latter resulting from the re4sidence of King Charles II in Bruges from 1656 to 1659, which are cherished.

Based on current prosperity and dynamics, it may rightly be hoped that the Guild will continue to exist successfully through centuries to come.

(ca 1375-1573)

From the beginning to the Lombaertheester

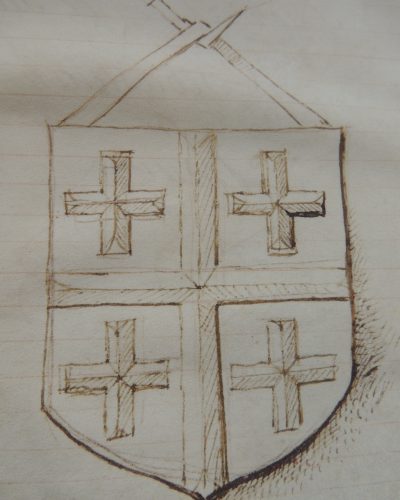

‘Since there is no foundation charter (anymore), the exact foundation date of the Saint Sebastian Guild in Bruges, hereafter referred to as ‘the Guild’, is not known. It used to be said that Guild brothers had already participated in the crusades, but this is a myth that may have been inspired by the Jerusalem cross that adorns the Guild’s coat of arms.

The oldest date where reference is made to the Longbow Guild can be found in an archive document from 1491. It mentions an agreement that the Guild concluded on June 13, 1396 with the Bruges Friars Minor to dedicate masses in a side chapel of their monastery church. The Guild probably originated a few decades earlier, perhaps around 1375. Indeed, in the Bruges city accounts of 1379, one finds for the first time the mention of ‘ghesellen with handboghen’.

Although the roots of militia guilds can be found in urban militias, their military significance at their inception in the fourteenth and their glory period in the fifteenth century was limited or nonexistent. They emerged as lay fraternities, by analogy with the craft guilds. Although the St Sebastian Guild brothers were mainly archers who were on call for the defense of the city and for military campaigns, the Guild itself was not a military corps and did not act as such. The urban archers were free to decide whether or not to join this relatively exclusive brotherhood. Spouses and children could also join the Guild, just like nobles and even clergy.

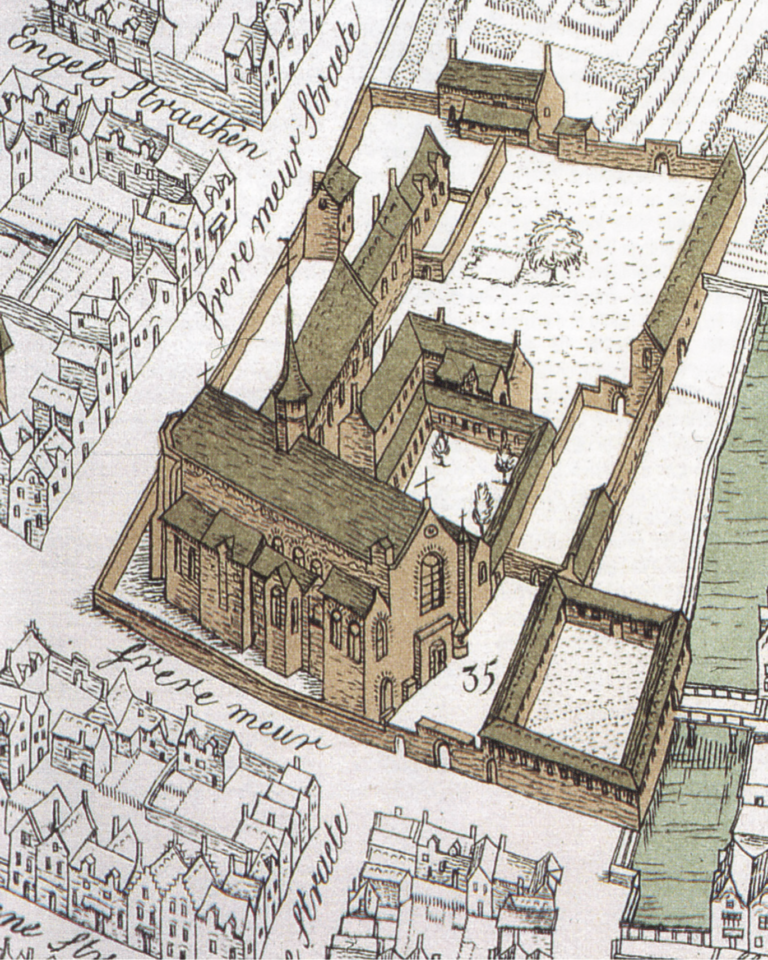

Besides practicing their hobby, parrot shooting, and organizing festivities around it, the Guild brothers were also able to meet their charitable and religious commitments. In the side chapel of the Friars Minor monastery mentioned above, which was arranged at the expense of the Guild, dedicated masses and the veneration of the patron Saint Sebastian contributed to their own salvation and that of their deceased colleagues and relatives.

The threefold structure of the Guild board (called the Oath) reflects the three important elements in the creation of the Guild: city militia (Captain and Lieutenant), lay fraternity ( two Deans) and prize shooting (‘King’ or Sire).

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the six Bruges armed guilds were at the epicentre of social life in the city. Of these guilds, only the Guild of Saint Sebastian has managed to preserve the patrimony and old traditions, to remain uninterruptedly active until today.

In the first centuries, wives of Guild brothers also became members, not to take part in the shootings but to take the Guild’s charitable works to heart. As the religious charitable character declined and the Guild evolved increasingly into a sports association and circle of friends, fewer women joined. The last women were registered in 1801.

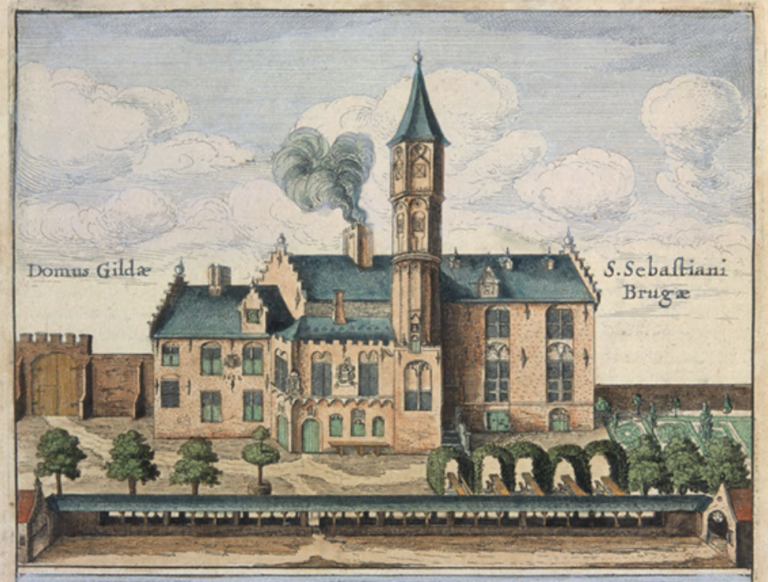

In addition to the chapel in the Friars Church, from 1454 the Guild had a house and grounds in the Rolweg, the Handbogenhof. In 1573, under the leadership of Guido Laurijn, the Lombaertheester was purchased. This large town mansion was probably built in 1546, in a somewhat old-fashioned Gothic style and radically rebuilt in 1570 by Cornelis de Blois. Until today, this beautiful building in the Carmersstraat has been the scene of all Guild activities, weekly shootings and festivities around the feast day of Saint Sebastian (20 January) and in June with celebrations of the jubilees for those with 25 or 50 years of membership.

(1573-1798)

Cloudy times and an unexpected lucky event (1573-1798)

Shortly after the Guild moved into the Lombaertheester, Bruges came under a Calvinist regime that lasted from 1578 to 1584. In 1578 the silver and gold artefacts in the Guild’s chapel were claimed and handed over to the city council, including the heavy silver reliquary with the skull fragment of Saint Sebastian, weighing almost 2Kg. This had been donated to the guild by Pope Martin V in 1428. Of the original silver, only the king’s bird and sceptre have been preserved in the Guild to this day.

Also in 1578, the church, including the Guild’s chapel and part of the Friars monastery were demolished. The Franciscan friars had manifested themselves in their sermons as strong opponents of the new Calvinist religion and paid the price.

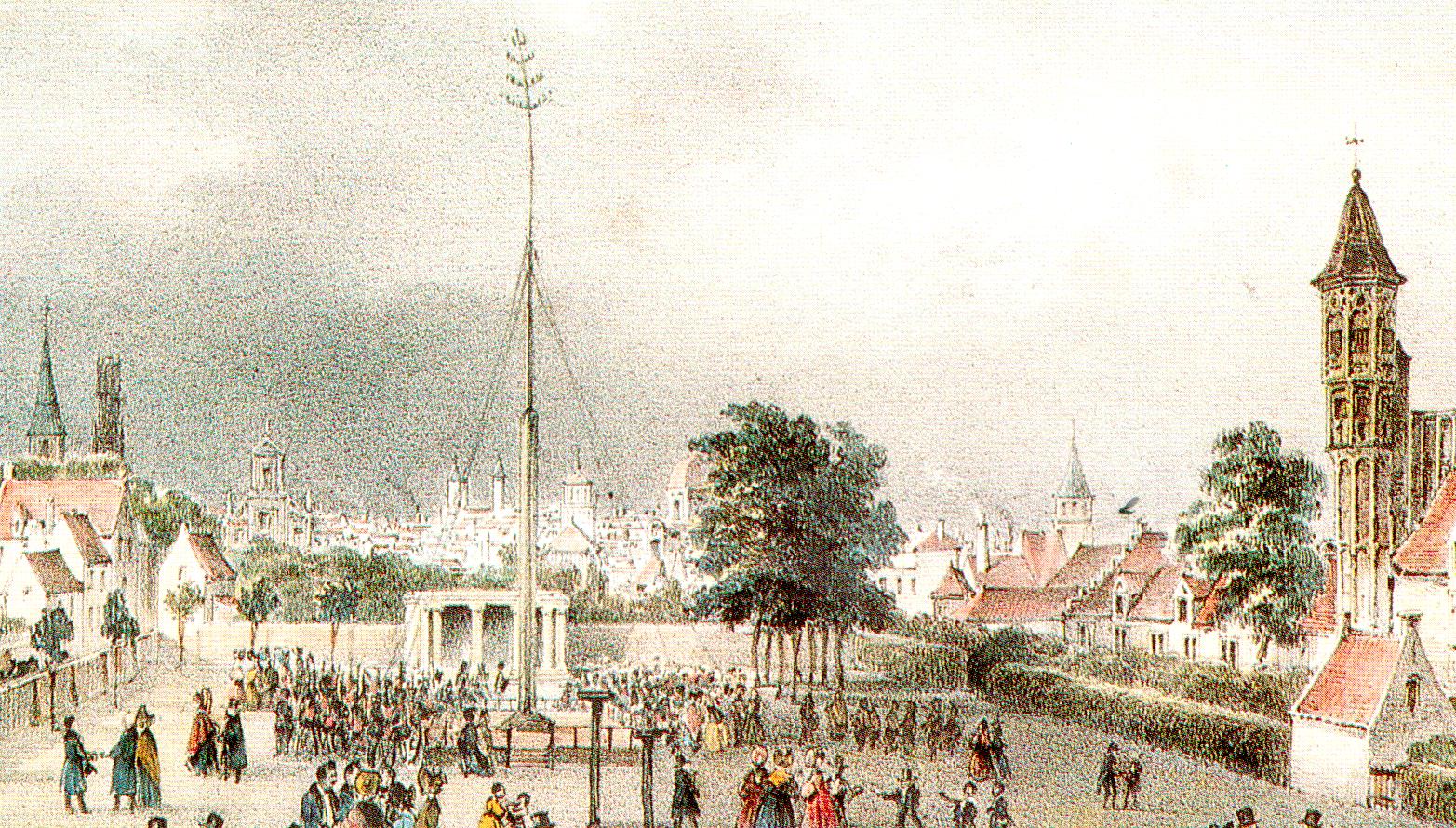

When, in England, the conflict between Parliament and King Charles I Stuart turned into a bloody civil war and the king beheaded in 1649, his eldest son, Charles II, had to leave England in 1651. He spent years in exile on the European continent, fleeing the new ruler, the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. In the spring of 1656 Charles II arrived in Bruges, later joined by his younger brothers, Henry, Duke of Gloucester and James, Duke of York. They quickly became interested in the Bruges militia guilds. They preferred archery, with which they were more familiar in England. Charles II, his brother Henry and some English officers joined the Saint-Sebastian Guild in August 1656 and regularly took part in their activities.

During his stay in Bruges, Charles II had some 400 English volunteers recruited with a view to a potential return to London. This First Regiment of Foot Guards, founded in Bruges, was later deployed on various battlefields and contributed to the defeat of the French Grenadiers of the Garde Impériale in Waterloo in 1815. From then on it was renamed ‘The First or Grenadier Regiment of Foot Guards’. They took over the bearskins from the French Grenadiers. Since 1877, as the Grenadier Guards, they are still active, not only to raise the Royal Guard at Buckingham Palace but in many British foreign military operations.

Charles II left Bruges for good in March 1659. After Cromwell’s death, he was able to ascend the English throne in 1660 and reigned until his death in 1685. He had not forgotten his generous reception in Bruges. In 1662 he donated a large sum to the Guild that was used to build the majestic King’s Hall, almost doubling the size of the Guild hall. His bust still adorns the monumental fireplace.

This unforeseen twist of history was the beginning of our privileged relationship with England and Scotland (the Royal Company of Archers), British Royalty and the Grenadier Guards.

(1798-1944)

Nearly the end ... and yet resurrected, but with less religion

In the decades after the demolition of the Guild chapel in the Friars Monastery, the Guild brothers continued their religious activities in various churches and monasteries in Bruges, until their own chapel was built in 1686, attached to the existing Guild building.

After the occupation and incorporation of the Netherlands into the French Republic, all brotherhoods and guilds, considered as relics of the Ancien Régime, were legally dissolved and their property seized. In 1798 the Lombaertheester was put up for public sale. The survival of the Guild, already centuries-old, was under threat. Some enterprising Guild brothers founded a new company ‘Vyncke-Van Outryve-Van den Kerckhove’ that would buy up the property. Petrus Vyncke did indeed succeed in buying the Lombaertheester for 45,000 Fr. Immediately afterwards, shooting activities were resumed.

When Napoleon scaled back the most fundamentalist republican measures, the Guild was able to buy back the property of Vyncke & Co. in 1809. The painted portraits of Petrus Vyncke and Pieter van Outryve still adorn the walls of the King’s Hall, which was enlarged once more in 1856.

Lists of members, records of the Oath and account books attest to the quiet resumption of Guild life and of the construction and other activities after this existential episode. The Guild chapel continued to be used in the first half of the nineteenth century and the Guild appealed to a Provost. The last Provost was the well-known priest and politician Léon de Foere (from 1833 to 1850).

In 1834 the Guild was recognized as ‘Royal’ by king Leopold I. In 1868 the Oath decided to abolish the religious character of the Guild. The Guild remained extremely liberal and anti-clerical for almost a century and in 1883 presented itself as ‘Saint-Sébastien, société royale, loyale et libérale’. The built-on choir of the chapel was demolished in 1900 by the city architect Delacenserie on the occasion of a general restoration of the Lombaertheester.

A festive banquet continues to be held on or around the feast day of Saint Sebastian (20 January), albeit without the former four Friars Minor who used to be invited, since they have long since disappeared from Bruges.

(1944-present)

Growth and prosperity in recent decades with a hopefully long and grand future

Successive Captains-General Henri Godar (1944 – 1979), Willy Van Poucke (1983 – 2002) and Hubert François (2002 – 2018), with the cooperation of many Guild brothers, laid the foundation for the great flourishing of the Guild that, today has led to a dynamic Guild ‘in top condition’, perhaps unequaled at any time in the past.

- The membership base has diversified. All philosophical, political, or religious beliefs can be represented. In 1973, Dutch was reintroduced as the official language.

- Target shooting was reinstated and an ’emperor’ competition for the best target shooter is organized every year.

- The building heritage and the 1ha garden are still maintained with great care and restored when necessary. Since 1958 the property has been listed as a protected monument.

- The Guild house is open to visitors as a museum. Valuable paintings, silverware and other art objects are displayed, as well as numerous other memories of its rich past, including visits and the honorary membership of British and Belgian monarchs. Queen Mathilde, then Princess in 2008, Princess Astrid in 2016 and Prince Laurent in 2019 are currently successors in the list of royal honorary members.

- The centuries-old archive is carefully preserved and managed on site by the archive committee, which has taken the inventory and, in recent years, digitization to heart. The oldest available archival item dates from 13 December 1416. Six hundred years later, in the autumn of 2016, an exhibition was established and a book about 600 years of Guild archives was published.

- Long-standing ties with the British Royal Family and the Grenadier Guards have been strengthened. New contacts were made with the Royal Company of Archers, who act as the bodyguard of the Queen in Scotland. Queen Elisabeth II visited the Guild in May 1966. In September 2006, the 350th anniversary of the Grenadier Guards was celebrated with great splendour in Bruges, with HRH Prince Philip the Duke of Edinburgh attending. A number of Guild brothers were actively involved in the planning (from 2008), the realization and inauguration of the Flanders Fields Memorial Garden in London in 2014.

This historical overview undoubtedly shows that we can rightly hope that the Guild will continue to exist for the twenty-first century and many centuries after, with respect for our rich history, adapting where necessary and with our old adage as a guideline : ‘Live with the past but not in the past’.